As the Popularity of Transloading Continues to Grow, Operators Should Consider Sliding Vane Pump and Gas Compressor Technology for Low Maintenance Costs and High Energy Efficiency

By Ted Ratcliff

Introduction

Transloading is the practice of transferring products between “modes” of travel, be it from refinery to terminal, terminal to supplier, supplier to storage facility, or supplier to end-user. The products that are typically transloaded can run the gamut from liquid chemicals and petroleum products, to animal fats and vegetable oils, to raw and semi-finished commodities such as grains and dairy products. The modes of travel include marine, pipeline, rail, air and truck. Goods, whether raw or finished, rarely ever travel directly from their source to the end-user.

For the purpose of this discussion, we will focus on transloading that involves the transfer of products or raw materials from railcar to truck. Transloading allows shippers and their customers to enjoy much of the cost benefits of rail transportation without having a rail siding at their door, which can be an expensive proposition, and for many companies, a physical impossibility. In most instances, a transload facility operator, third-party logistics company or transportation broker facilitates transloading for both the shipper and the consignee. These companies coordinate truck and rail connections and frequently offer inventory management and facilitate storage and delivery.

The main objective of transloading is to place the goods as close as possible to the point of final processing, packaging and consumption as economically as possible. Therefore, transloading can occur at any place a truck can pull up to another truck or a train. In a typical transaction, a bulk shipment moves by rail to a transload facility where it is offloaded with specialized pumping equipment that has the necessary operational characteristics to handle the specific commodity. The bulk product can then be scheduled for delivery in smaller quantities to the consignee for further processing or delivery directly to an end-user. An advantage of transloading is quick response to replenishment of inventories with transportation costs kept to a minimum, while it also allows companies to accelerate turnover and reduce inventory costs.

Since transloading requires the handling of the goods at various points during the supply chain, there is an inherent risk of damage or the loss of expensive product that can potentially harm the environment or personnel. Shipping vessels must also be completely cleared of product during the transloading process. With all of these factors in mind, it is imperative that the proper equipment be utilized during the transloading process. This white paper will focus on the proper types of pumps and compressors that are needed, especially for the transfer of chemicals, petroleum products, animal fats, vegetable oils and other liquid commodities.

The Challenge

The practice of transloading has grown rapidly in recent years, so much so that it now has its own trade association. The Transloading Distribution Association (TDA), West Linn, Oregon, USA, represents the interests of the transloading industry as it relates to business and political leaders, while positioning transloading as the preferred method for efficient distribution of product in the 21st century. Currently, the TDA has more than 200 members throughout the United States, Canada and Mexico.

As mentioned, the main challenge for shippers is moving their products in the safest manner while also minimizing the risk of costly and environmentally damaging product spills. Recently, however, economics have played an increasingly important role in a shipper’s decision to move product via a transloading operation. These economic pressures have come to bear in the form of driver and equipment shortages, record high fuel costs found in long-haul trucking and increased demand for shipping capacity.

A producer relying on long-distance trucking to service a set of customers faces many difficulties. The most significant one is the likeliness of empty travel for return trips, in addition to the need for a large fleet or trucks in order to ensure service frequency. Adopting a transloading operation can allow these shippers to rely on a smaller fleet of trucks that need to travel shorter distances, which may also allow them to make several deliveries a day. A transloading facility can also offer a large number of value-added incentives for the shipper, including storage, blending, packaging, consolidated invoicing, combined product shipments, bar-coding and labeling.

For shippers that are considering switching from a single transportation mode to transloading, there are some useful benchmarks that can help guide their decision. A main consideration is whether the distance the product needs to travel is great enough to make the cost of transloading worthwhile.

As a transloading “template” of sorts, 300 miles is generally the differentiation breakpoint for transloading, or essentially the distance a long-haul trucker can safely and efficiently travel in one day. Another thing that should be taken into consideration is the transportation and handling costs associated with trucking and transloading. In a true bulk-transport transloading operation, a shipper can oftentimes ship out four truckloads of product on a railcar while typically paying the equivalent of only two-and-a-half truckloads in price.

According to the TDA, there are currently around 650 transloading terminals in the United States, with more in the works. The TDA forecasts double-digit growth in throughput by its members through 2015. The average number of available railcar positions per transloading facility is 50. If these estimates are correct, then there is room for more than 32,000 tank cars to be unloaded at any one time. Granted, that full capacity will probably never happen, but these numbers do offer an idea of the potential size of the market. Using these estimates and assuming only a 60% utilization factor, each facility would require three to five pieces of off-loading equipment to keep up with demand. At the lowest level, that would be almost 2,000 units on the ground.

With that said, while transloading may make the most sense for a shipper from both an economical and logistical standpoint, the world’s most efficient transloading operation will not function successfully if the pumping and compressor equipment needed to necessitate the transloading process does not work effectively.

The Solution

Fortunately for the vast array of shippers who are implementing transloading operations, there is an easy solution to their product-transfer needs. It is the complete line of sliding vane pumps and reciprocating-gas compressors from Grand Rapids, MI, USA-based Blackmer®. Blackmer – which is part of the Dover Corporation’s PSG, Redlands, CA, USA – is the global leader in transloading solutions since its sliding vane pumps and compressors are highly energy efficient and eliminate many of the maintenance concerns that are inherent in other pump and compressor styles.

The versatility of Blackmer’s sliding vane technology is what makes these pumps ideal for transloading applications. Blackmer sliding vane pumps are self-priming, designed to run dry for short periods, and their high suction makes them ideal for line-stripping. They are available in cast iron, ductile iron and stainless steel models with special elastomers that make them compatible with the handling of an impressive array of products. For self-loading trucks, the pumps come with port sizes to 4 inches and have maximum working pressures up to 175 psi (12.1 bar). They can reach speeds of 1,200 rpm with both PTO and hydraulic drive capabilities. For transloading applications that involve stationary and portable onsite pumps, by manifolding the railcars, the flow rates are basically only limited to the receiving capacity of the system. Certain lines of Blackmer sliding vane pumps are also available in a sealless design for applications that require zero shaft leakage.

The vanes in a sliding vane pump slide freely into or out of slots in the pump rotor. When the pump driver turns the rotor, centrifugal force, rods and/or pressurized fluid causes the vanes to move outward in their slots and bear against the inner bore of the pump casing, forming pumping chambers. As the rotor revolves, fluid flows into the area between the vanes when they pass the suction port. This fluid is transported around the pump casing until the discharge port is reached. At this point the fluid is squeezed out into the discharge piping.

This simple pumping principle, which has been an industry standard for more than a century, allows Blackmer’s sliding vane pumps to handle numerous types of products safely and efficiently. Among these are clean, non-corrosive industrial liquids and petroleum products; liquids ranging in viscosity from thin solvents to heavy oils; hazardous fluids; biofuels; non-lubricating solvents to highly viscous liquids or abrasive slurries; corrosive or caustic fluids; and inks, paints and adhesives.

Like the sliding vane pump, Blackmer’s reciprocating-gas compressors have been designed with liquefied gas transloading operations in mind. A compressor draws vapor from the storage vessel and boosts the pressure into the top of the rail car. The increased pressure in the rail car and slightly decreased pressure in the storage vessel results in a pressure differential between the two tanks that will easily push the liquid from the rail car to storage. The result is fast and quiet liquid transfer with no NPSH or cavitation problems. These compressors are equipped with high-efficiency valves, ductile-iron cylinders, self-adjusting piston rod seals and other robust features.

Blackmer’s LB Series compressors not only evacuate a railcar or truck tank, they can recover vapors, as well, which is like adding 3% capacity to every load. They are available with transfer capacities ranging from 40 to 640 U.S. gpm (150-2,420 L/min). LB compressors are designed to handle transfer and recovery of propane, butane,

LPG and anhydrous ammonia. Blackmer’s HD Series compressors can handle the transfer and recovery of carbon dioxide, refrigerants, sulphur dioxide, chlorine, vinyl chlorine, natural gas, nitrogen and other gases.

The portability of Blackmer’s sliding vane pumps and compressors has also allowed many shippers and operators of storage facilities to create moveable skids that allow the pumps and compressors to be shifted around a facility to perform transloading operations. These “transloaders” can be placed between two railcars on a siding if product needs to be pumped out of one and into the other, or positioned between and truck and railcar to facilitate the transloading process.

For an example of how effective a transloading operation featuring Blackmer pumps can be, consider the case of Seeler Industries. Seeler operates the 3 Rivers Terminal in Joliet, IL. This 100-acre facility features 17 storage tanks and 15 blend tanks. It has become one of the Midwest’s leading storers, handlers and packagers of hydrogen peroxide, along with other industrial liquids like caustics, amines, glycerin propylene, glycol and chemical de-icers.

The 3 Rivers Terminal is served by seven truck-loading racks and 42 railcar-unloading positions. These racks and railcar positions enable Seeler to offer transloading services to its customers. To optimize its transloading options, Seeler installed a series of Blackmer STX3 and SNP3J sliding vane pumps, which are ideal for use in terminal transfer applications because their stainless-steel construction makes them compatible with the chemicals, solvents, caustics, sulfates and acids that the terminal handles on a regular basis.

To increase its transloading options, Seeler also had a Blackmer SX3 sliding vane pump mounted on a portable cart that is moved wherever it is needed in the vast 3 Rivers facility. This pump features a gear-reducer that allows it to run at two speeds—90 to 100 gpm when offloading a railcar and 60 gpm for drum and tote filling. The pump’s engine drive also allows it to be used even when there is a power failure.

Conclusion

While transloading in some form has been around since the age of steam engines and horse-drawn tank wagons, it has seen a marked resurgence in the past decade. According to some estimates, the volume of transloaded cargo has grown by 50% since 2000. This increase in transloading coincides with the realization by many shippers that the cost and efficiency benefits of this multimodal approach to moving products in bulk can have an extremely positive effect on their bottom lines.

To ensure that the transloading process operates as smoothly and efficiently as possible, savvy shippers and storage-facility operators are turning to Blackmer’s various lines of sliding vane pumps and compressors to maximize the process. These pumps are up to the task because their design allows them to not only clear a truck or railcar, no matter the nature of the product, but to do it in a safe manner that protects both the environment and facility personnel.

Operators at this chemical distribution/storage terminal facility transload hydrogen peroxide from a railcar to a transport via a Blackmer sliding vane pump.

This transloading application features Blackmer compressors transferring LPG from railcars to transports.

The sliding vane principle

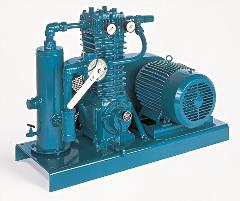

Blackmer LB Series compressor

[Sidebar]

Centering on Centrifugal

Blackmer also has the answers for transloading operations that involve the use of centrifugal pumping technology. The design of Blackmer’s System One® Centrifugal Pumps makes them capable of pumping several thousand gallons of product per minute, which is a crucial consideration when multiple railcars need to be loaded or unloaded at one time. The System One pumps can meet these parameters because they have been designed around the seal and bearings, where 90% of pump failures occur. Their heavy-duty, solid, low-deflection shaft prevents common vibration damage and allows greater stability at the seal area to improve seal life. These heavy-duty shafts, bearings, seals and housings mean that the pump has been built to operate effectively and efficiently in the most extreme environments.